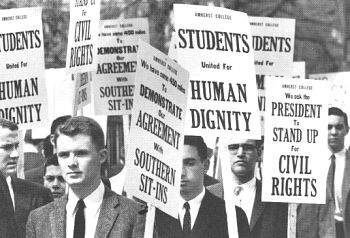

The mobs I talked about in “When Mobs Roam the Halls of Ivy” are real, and they–among other scary things–are a threat to academic freedom. Whether it is political pressure on boards or self-appointed bands of vigilantes policing the boundaries of politically correct speech, the forces that stifle open and unfettered inquiry on college campuses undermine everyone. It is not the exclusive province of one political stripe to protect the rest of us from the assault of the other side whose ideas are–axiomatically–unacceptable. The campus civil rights movements of the 1960’s would probably not have withstood the determined attacks that would be mounted today.

The real point of the Henry Drummond (the Clarence Darrow character in the 1955 Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee play Inherit the Wind) defense of academic freedom (“the right to be wrong“) is revealed when with Matthew Brady (William Jennings Bryan) takes the witness stand and Drummond goes on the attack: “I’m trying to stop you bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States.” Lawrence and Lee wrote ITW at the height of Senator Joe McCarthy’s crazed hunt for Communists, a purge that viciously pursued academics and intellectuals whose ideas and writings placed them outside the Senator’s narrowly defined strip of acceptable thought. It was a parable for its time, but the 1925 trial of Tennessee teacher John Scopes for violating the Butler Act was one of literature’s most inspired dramatic backdrops.

Henry Drummond was on the side of progressives for whom bigotry meant barring the teaching of evolution, but he would have been just as comfortable defending campus civil rights protests or anti-war demonstrations in the 1960’s. Or Columbia President Lee Bollinger’s decision to host Iranian President Ahmadinejad. Bollinger introduced Ahmadinejad with a blistering attack on the very fabric of regressive Iranian theocracy. Bolliinger, it could be argued, was not a very gracious host, but he at least enabled the kind of politically unpalatable speech that academic freedom is designed to protect. But what about the other side? Would Drummond have been equally passionate about the pressure brought by progressive Rutgers faculty members to rescind the invitation to Condoleeza Rice’s to deliver the 2014 commencement address, “because of her role in the Iraq War.” If not, it would have been a missed opportunity to point out that academic freedom is a two way street, and the door that leads to it is either open or closed. There is nothing in between.