It dawned on me during the recent saloon brawl at the University of Texas over exactly when and on whose terms President William Powers would leave office that the nation’s top research universities could succumb to the rule of self-interested and unaccountable mobs. Texas joins a growing list of public universities where governing boards have tried to remove presidents—one of the few duties that virtually every state assigns to boards—only to find themselves demonized as cabals. It can’t be a cabal if you are the public authority designated to make those decisions. What began in 2012 as a media spectacle–triggered by the short-lived firing of University of Virginia President Teresa Sullivan and fueled by Twitter and Facebook campaigns worthy of Tahrir Square—has become trendy as the number of legitimate governance decisions undone by academic vigilantism has tacked alarmingly upward.

The Texas case is notable because there is pressure coming from two directions. Heavy-handed political influence from conservative allies of Governor Rick Perry, who are unconvinced of the need for a research mission at UT-Austin and want the university’s Board of Regents to force the flagship university to abandon—or at least starve—it, has so damaged the board that one of them is under investigation for possible impeachment. On the other side, faculty and student groups who want Powers to stay have taken to the media to build public support for their case. Many of them were attending a symposium about online education when a deal that would allow Powers to remain in office was announced. The ensuing celebration was boisterous and probably helped the cause of those who are demanding the impeachment of Perry’s allies.

The dust-up with the Texas Board of Regents is only the most recent example of how difficult university governance has become. Even unremarkable commencement ceremonies came under assault earlier this year as a dozen high-profile speakers were disinvited by university administrators who bowed to pressure groups. What could have riled the unruly mobs? Among those who threatened the sensibilities of the Class of 2014 were IMF Director Christine Lagarde and a critic of radical Islam who had survived mutilation in fundamentalist Muslim East Africa. All were excoriated in public. Faculty groups, student newspapers, bloggers, and anti-defamers rose up in protest that views so divergent from their own should be expressed under a banner proclaiming truth or veritas, or something like that.

So much for academic diversity and the fearless band of heroes and martyrs that, Daniel Coit Gilman, the first president of Johns Hopkins—the first American research university—promised would “prosecute learning” regardless of consequences. It is probably not what John Adams had in mind in 1780 when he wrote in the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts of the moral duty of society to cherish the interests of “seminaries of learning.” It does not cherish their interests to pay attention to the digital-age equivalent of epithets scrawled on subway walls. But that is what, increasingly, masquerades as academic governance. Unchecked, it is a trend that imperils ours, the best universities in the world.

Religious institutions aside, there are really only two ways to run a university. In Europe, universities are state-run affairs. Professors are civil servants, and Ministries of Education make all of the important decisions. University presidents and other administrators are chosen in faculty elections, but they are in truth labor leaders who are beholden to the narrow interests of professors, not to students or even to society. The sorry state of European research universities (despite a five hundred year head start, only eleven of the top fifty research universities in the world are European; thirty-one are North American) is a testament to the failure of that model.

American universities (especially public universities) were conceived differently with appointed trustees or regents who are accountable to society. In the U.S. system, boards have ultimate legal authority to choose top administrators, approve faculty appointments and guarantee academic freedom. Presidents are then given considerable autonomy in the day-to-day running of their institutions. That autonomy is shared with faculty members who are expected to make expert decisions about academic matters in a system of governance outlined in a 1915 declaration of academic freedom that marked the founding of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP). Autonomy is so ingrained that shared governance is sometimes willfully–almost comically–misconstrued to mean that administrators work for the faculty and that governing boards are at best irrelevant to a university’s mission.

In normal times it probably does not matter much, but these are not normal times. Forty million Americans owe 1.2 trillion dollars in student loans. One in seven borrowers defaults within two years of leaving college. Tuitions are rising at twice the rate of inflation while family incomes are flat. Americans have lost confidence that affordable, excellent college education is within their reach. Under pressure from both the left and the right, political correctness has become a bludgeon used to beat back the free exchange of divergent views on campus. Change is needed, and there are transformational ideas that can help universities get back on track. But, as former University of Michigan President James Duderstadt has pointed out, change will be slowest at the institutions where shared governance is strongest. The mobs could care less.

Who has the interest of society uppermost? Presidents are accountable, but most have careers to advance. They have powerful incentives to behave like stewards of the status quo. Not faculty. Many are deluded about the need for someone to be in charge at all. Not students themselves. They have even narrower interests and lack perspective. The AAUP’s 1915 declaration acknowledges that governing boards are responsible for society’s interests. Not all boards are good at that, and the bad ones should be replaced. It is not clear what led to the Texas Regents’ decision to fire William Powers. Conflicts with trustees can simmer for years before boiling over and leading to a president’s ouster. The publicly stated rationale for a firing is not always the real one, but Governor Perry’s fascination with a shortsighted agenda promoted by the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation certainly played a role. As bad as those ideas would be for a great university, it is hard to argue that the long-term interests of institutions like the University of Texas are served by polling unaccountable mobs.

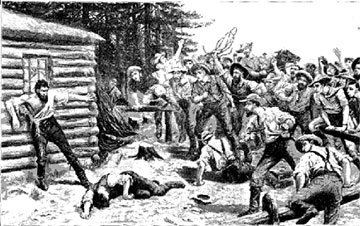

College presidencies are derailed all the time. There were dozens of firings last year. Hundreds of people who represent unpopular points of view made commencement addresses. So why such a ruckus over a Texas firing or Christine Lagarde’s commencement invitation from Smith College? Mobs have become well-heeled Internet marketing experts. It is no accident that supporters of William Powers were in contact with Teresa Sullivan’s supporters at The University of Virginia, where the art of demonizing and isolating board members was perfected. It is only a matter of time before roving bands of torch-waving villagers realize that by storming the gates they can impose their interests and the well-armed mobs start roaming the Halls of Ivy.

The result will be the steep descent of the best American universities into a soup of international mediocrity when global leadership is needed. The contract between academia and society is strong in this country. It was renewed in President John Bascom’s 1879 “Wisconsin Idea” that spoke of the university’s duty to reach into every family, and Rafael Reif’s soaring 2013 MIT inaugural that warned of the dangers to society of driving an economic wedge between universities and the American public. It is diminished every time a mob is rewarded for undermining legitimate authority. Universities are a national treasure to be cherished, and strengthening the quality of their governing boards also strengthens the social contract. Mobs like to attack strong boards as corporatist, but there is nothing corporatist about acting to ensure that institutions are healthy and vibrant. There is no sport in using Twitter to amplify personal attacks on trustees and administrators. It is a celebration of mob rule.