Let’s imagine a pill. I’ll call it e-pill. It’s available to every young adult who wants it — probably a benefit of some program to link health care and education. E-pill has one effect: it permanently rewires brains to store, understand and effectively use knowledge equivalent to the general education requirements at a good American university. You know what courses I am talking about: science, math, history, philosophy, art, social science, writing, and literature. No side effects. It does not make you any smarter, but if you’ve taken e-pill, you have a lock on credit for English 101 and Intro to American History. No downside to the pill at all except for this: you have to forgo the classroom experience.

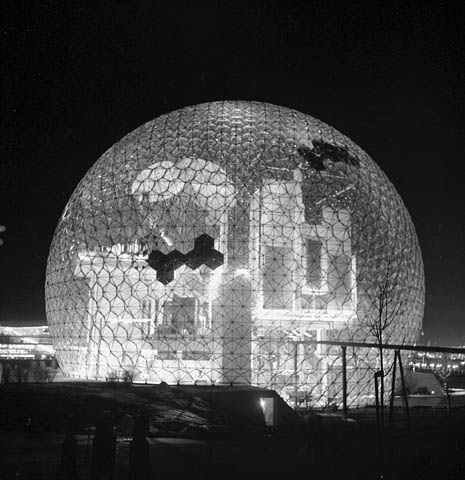

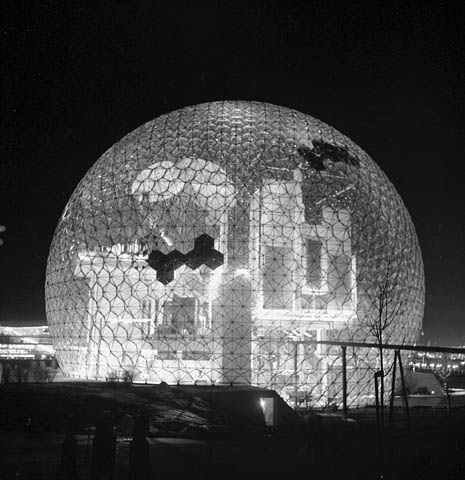

Thinking about e-pill clarifies something that has been on my mind a lot these days: ephemeralization of American colleges and universities. Ephemeralization is a term that Buckminster Fuller used to capture the economic concept of dematerialization. In effect, ephemeralization means doing more with less.

The National Conference of of State Legislatures just issued a report that makes it clear the extent to which public universities will have to do more with less over the next several years. According to State Higher Education Executive Officers:

Appropriations per student remained lower in FY 2009 (in constant dollars) than in most years

since FY 1980.

Tuition increases — which now average 37% of revenues — have made up for some of the shortfall, but as Delta Project data makes clear, although increased tuition may cover lost revenue, it does not necessarily find its way into instructional budgets. Public institutions have been using stimulus funds provided by the 2009 Federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to keep the wheels on. ARRA funds will disappear soon. All the while, students are pouring into dozens of campuses like the University of Central Florida where access is paramount.

The lead article in today’s Chronicle of Higher Education, was a jaw-dropping summary of the budget shortfalls awaiting the State University System of New York and other systems where state finances are so broken that higher education funding will be disastrously inadequate for years. Maybe decades. Short of rolling over and shedding both students and programs, dematerialization is the order of the day for most of us in public universities.

As I pointed out in last week’s post, there are swirling financial misconceptions that — if acted upon — could actually make matters worse. This is not the time, for example, for an aspiring public institution to undertake a large research commitment in the blind hope that research revenue would help the budget.

What does this have to do with e-pill? This is a time to take a serious look at the value proposition for American universities. If there is a way to get the unnecessary cost out of the general education requirements, it would have an enormous impact on the economics of running a public institution. Universities — particularly research universities — are under-reimbursed for the cost of offering courses that do not need to be taught in the traditional , expensive, bricks-and-mortar way. I mentioned the University of Central Florida above, because as the third largest university in the country, they have already shifted a substantial portion of their introductory load to online delivery — not exactly an e-pill, but the marginal cost per student in an online course is a tiny fraction of the cost for campus-based delivery.

If the marginal cost were actually zero (the e-pill scenario), then what would be the rationale for charging anything for the first two years of a university education? The argument that was made shortly after the American Civil War was that the social experience of attending a university was worth the price of admission. It was not a winning argument, and the structure of higher education in the U.S. was forever changed as a result.

The experiment should be easy enough to run. Let’s set two prices. The first price, a nominal fee, reflects the true cost of the general ed requirements when they are offered efficiently using modern technology — costs that are unburdened by subsidies to research, athletics, and bureaucratic offices that add little value to a student’s education. The second price — the deluxe treatment — reflects the true cost of the on-campus experience. Virtually all of the value for the high price on campus experience is from activity outside the classroom, and because there has been an effective dematerialization for English 101, the income from families who have the wherewithal to pay for first-class tickets can be applied to other institutional priorities. Maybe even the upper division courses where smaller class sizes and dedicated instructional budgets might have a beneficial impact on a student’s education.

Vendors of proprietary Unix™ servers had to face this same problem a decade ago. Why would a customer pay the high-margin premium prices for HP-UX™, Solaris™, or AIX™, when there was a “free” alternative? The answer, it turned out, was that customers paid for value. The smart companies figured out that the high-margin, high-expense proprietary Unix business was different from the low-margin open source business. Smart companies figured out how to make both businesses work.

This is the opportunity for ephemeralization. Since doing more with less is inevitable, why not turn our attention to it? We will never get an e-pill, but we might be able to squeeze half the cost out of the rapidly commoditizing general education requirements.

The question for public universities is what to do when the crossover point is reached — when the value to students exceeds the cost of delivery. I asked Arizona State president Michael Crow exactly this question, and, without skipping a beat, he told me he would like to do: “Let’s figure out what we are the best at, and make that available to as many students as possible. If ephemeralization is inevitable, what other value propositions change what universities will look like when we reach the crossover point?