I’ve been spending more time with alumni. Zvi Galil, the new dean of computing at Georgia Tech — my successor — has been on a national tour to get acquainted with recent graduates. I accompany him whenever I can to make introductions and to generally help smooth his transition. Not that he needs it. Zvi was dean of engineering at Columbia for many years and knows how to get alumni to talk honestly about their undergraduate experiences. We were having lunch with a group of recent graduates when I heard Zvi ask someone at the end of the table, “What’s the one thing you wish we had taught you?”

The answer came back immediately: “I wish I had learned how to make an effective PowerPoint™ presentation!” If the answer had been “more math” or “better writing skills” I would have filed it away in my mental catalog of ways to tweak our degree programs. It’s a constant struggle in a requirement-laden technical curriculum — even one as flexible as our Threads program — to get enough liberal arts, basic science, and business credits into a four year program, so I was prepared to hear that these young engineers wanted to know more about American history, geology, or accounting. After all, I am a former dean. I had heard it all before.

But PowerPoint? Everything came to a stop. Zvi said, “PowerPoint!” It was an exclamation, not a question. Here’s how the rest of the conversation unfolded” “Look, the first thing I had to do was start making budget presentations. I had no idea how to make a winning argument.” From the across the table: ” Yeah, we learned how to make technical presentations, but nobody warned us that we’d have to make our point to a boss who didn’t care about the technology.” “It’s even worse where I work,” said a young woman. “Everybody in the room has a great technology to push. I needed to know how to say why mine should be the winner.” And so it went. This was not a PowerPoint discussion. We were talking about Big Animal Pictures. If you understand Big Animal Pictures, you understand how to survive when worlds collide.

David Stockman directed Ronald Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) from 1981 to 1985. He was a technician. A financial engineer. He had a Harvard MBA, and spent the early part of his career on Wall Street with Solomon Brothers and Blackstone. It was a checkered career, and if you take seriously the accounts in his memoir of the Reagan years, he never really understood that he was caught between colliding worlds. Which brings me to Big Animal Pictures.

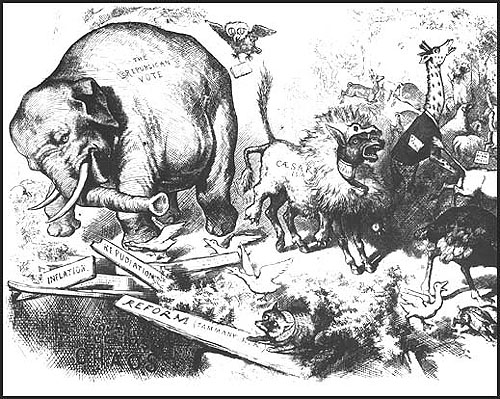

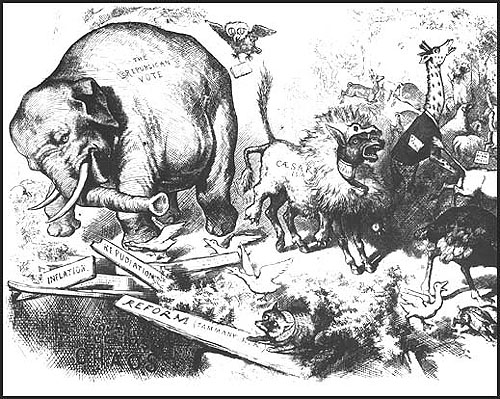

Stockman was a conservative deficit hawk who thought his job was to restore fiscal sanity. Reagan had beaten Jimmy Carter in part by painting the Democrats as financially irresponsible. David Stockman’s job was to fix that, and that meant budget-cutting. Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger thought that Reagan had been elected to restore America’s military might. Weinberger’s job was to pump more money into defense budgets. Stockman and Weinberger were on a collision course, and for a year they traded line-item edits to the federal budget. This was a technical duel. Stockman and Weinberger both had considerable quantitative skills. It was a bureaucratic game that Weinberger had learned to play when he worked for Reagan in California, but there was a deepening recession. In the end, it appeared that DoD would have to make do with the 5% increase that the White House was proposing. It was a spending increase that Stockman believed was unwise and unaffordable.

Weinberger’s proposal was 10%. Stockman could barely contain himself. It set up a famous duel in the form of a budget briefing with Reagan playing the role of mediator. It was going to be a titanic debate.

Stockman showed up with charts, graphs and projections. The stuff that the OMB Director is supposed to have at his fingertips. Weinberger came armed with a cartoon, and walked away with his budget request more or less intact.

Weinberger’s presentation was a drawing of three soldiers. On the left was a small, unarmed, cowering soldier — a victim of years of Democratic starvation. The bespectacled soldier in the middle — who bore a striking resemblance to Stockman — was a little bigger, but carried only a tiny rifle. This was the army that David Stockman wanted to send to battle. The third solder was a menacing fighting machine, complete with flak jacket and an M-90 machine gun. It was the soldier that Weinberger wanted to fund with his defense budget. Weinberger won the budget debate with Big Animal Pictures.

Stockman was appalled:

It was so intellectually disreputable, so demeaning, that I could hardly bring myself to believe that a Harvard educated cabinet officer could have brought this to the President of the United States. Did he think the White House was on Sesame Street?

Stockman and many analysts concluded that the episode revealed something deep about Reagan’s intellectual capacity. Maybe so, but I think it revealed more about Weinberger’s insight into what it takes to carry an argument when the opposing sides can each make a strong technical case for the correctness of their position: argue for the importance of the end result, not for the correctness of how you will achieve it. It is a classical colliding worlds strategy.

Michael Dell’s 1987 private placement memorandum for Dell Computer Corporation was a Big Animal Picture. Buying computers was a hassle when Dell started his dormitory-based business in 1984. By 1987, PC’s Limited had sold $160M worth of computers based on a simple strategy: eliminate the middle man, get rid of inventories, and give customers a hassle-free way to buy inexpensive, powerful IBM-compatible computers. In the midst of a stock market crash, Michael Dell managed to raise $21M based on a short document that ignored the conventional view that private placement business plans had to be highly technical:

Dell has sold over $160 million of computers and related equipment on an initial investment of $1,000. The Company has been profitable in each quarter of its existence, and sales have increased in each quarter since the Company’s inception.

Tacked onto the memorandum, almost as an afterthought were letters from customers — inquiries from people who were interested in buying computers from Michael Dell and testimonial from owners of his made-to-order PCs who wanted to buy more of them. It was short (45 pages with the letters attached) and, aside from a few pro-forma financials to explain what would be done with the new money, it was almost entirely devoted to painting a picture of what success looked like to Michael Dell.

A copy of the original Dell memorandum wound up on my desk in late 1998. At the time, my Bellcore department heads were struggling to define businesses that could either be spun out of the company or funded as internal startups. I was drowning in highly technical market forecasts and details of patent disclosures. Each new spreadsheet screamed: “Idiot! Just look at this equation. It’s obvious why our approach is better than everyone else’s.” One afternoon, in exasperation, I threw Michael Dell’s private placement memorandum on my conference table and said “Make me a presentation that looks like this.” The room got very quiet as they realized what was going on. I was asking for Big Animal Pictures.

We started four businesses within 18 months. Three were spun out and made a modest amount of money for the company and the founders. We ran one as an internal start-up. It did not do nearly so well. One of the key factors was that we could not duplicate Michael Dell’s Big Animal Picture.

This is not a lesson that engineers and scientists learn easily. In fact, when presented with overwhelming evidence that business decisions are seldom made on the basis of technical elegance and correctness, engineers retreat to the safer ground staked out by David Stockman: “Do you think we are on Sesame Street?” The answer is “Yes!” Successful engineers and scientists know all about Big Animal Pictures.

Paul R. Halmos was one of the great mathematicians of the 20th century. He studied the most abstract topics imaginable. One of his crowning achievements, for example, was to create an entire algebraic theory to describe mathematical logic, which was itself an abstract mathematical theory to explain symbolic logic. Symbolic logic was, in turn, an abstract explanation of the kind logic used by Aristotle, and Aristotle’s logic was the formalization of correct patterns of human inference. Halmos did not deal in uncomplicated matters.

How did Paul Halmos counsel young mathematicians to present their work in public?

A public lecture should be simple and elementary; it should not be complicated and technical. If you believe you can act on this injunction (“Be Simple”) you can stop reading here, the rest of what I have to say is, in comparison, just a matter of minor detail.

The mistake, Paul Halmos noted in his essay How to talk Mathematics is thinking that a simple lecture talks down to the audience. It does not. Halmos (or PRH as he sometimes called himself) seems to have understood worlds in collision. Of course, a simple lecture in PRH world might open with the phrase “…as far at Betti numbers go, it is just like what happens when you multiply polynomials,” so it’s a sliding scale.

No matter what you’re doing in the technical world, learning how Big Animal Pictures work is a valuable thing. I sometimes sit on review panels to decide on research funding. I recently advised a young scientist to use Big Animal Pictures. She had five minutes to present her work and I knew that the competition would be strong. Her first instinct was to jump into the technical meat of her research to give the reviewers a feeling for why her approach was better than other approaches. My advice was to not do that. I wanted her to literally give a BAP presentation that would inform the panel about the importance of her research and why they should care about it. I later found out that other colleagues had given her identical advice, which she apparently followed with great success.

And it doesn’t matter which of the colliding worlds you are on. BAPs are always a good idea. My colleague Wenke Lee was recently called upon to give a presentation on the state of computer security research to a group of mathematicians. It was all about how powerful mathematics can be used to exploit security flaws and vulnerabilities. Wenke resisted the temptation to dive into the technical details of botnet attacks. It is, after all, a subject he knows well and he probably would have had fun demonstrating his prowess. But here is how Wenke began his lecture.

He went on for another twenty minutes, but he really didn’t need to. Everyone got the point in the first thirty seconds.