Last year, I posted a cautionary article about the danger of letting opponents define you. If you thought I was overwrought when I suggested that “Picking Daisies” — the campaign ad that in all likelihood sunk Barry Goldwater’s presidential ambitions–had anything to do with public support for higher education, let me encourage you to spend the next hour watching this little number. It is called “College Conspiracy,” and it has one message: “College education is the biggest scam in US history,” I have made it easy for you. Just click play.

If you doubt that political warfare is being waged and that its aim is to provoke rage– to undermine public support for colleges and universities–just sit back as the ominous music leads you to the inevitable conclusion:

There is no reason that we the taxpayer should be funding college education.

It’s available on dozens of video sharing sites, including YouTube, which reports over two million views. That number is an order of magnitude larger than the number of copies of all books about how to improve higher education published in the last decade. Two million enraged viewers is enough to sway votes. It’s enough to pressure legislators. It is a large number.

There are close-ups of distraught faces and stories of foul greed:

Education ruined my life!

The camera shifts to the sympathetic interviewer:

They’re just vultures.

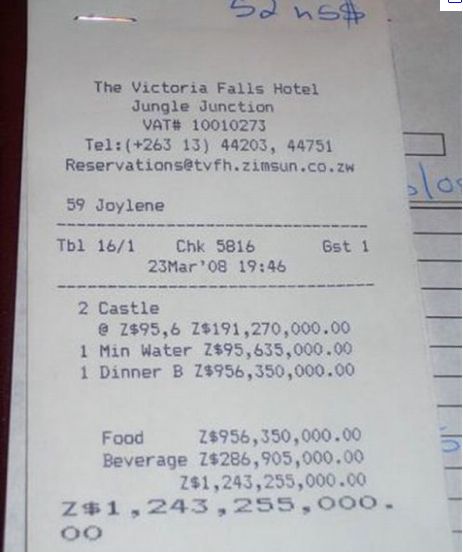

A clearly knowledgeable and steely-eyed commentator says that you don’t need a college degree to be successful and that the escalating costs of getting one is a harbinger of hyperinflation.

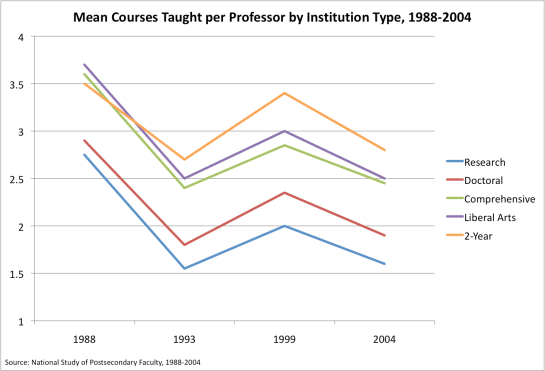

The narrator, with charts and graphs, argues that, like semiconductors, prices should actually be going down. For-profit colleges and traditional institutions are all painted with the same brush. They defraud students who, in exchange for exorbitant fees, end up with a worthless piece of paper that qualifies them for exactly the same low-paying jobs that high school graduates hold. Despite the Georgetown data showing that we have too few universities, steely-eyed commentator says that we have far too many.

You can pack a lot of disinformation into an hour. It took just thirty seconds to sink Goldwater. The problem is that “College Conspiracy” intermingles facts with distortions and tortured logic.

- Student debt now exceeds credit card debt: true

- Institutions engage in reckless capital spending that impresses prospects but adds nothing to the value of an education: true

- Multimillion dollar packages to coaches and an emphasis on the entertainment value of intercollegiate sports distorts and corrupts academic missions: true

- Tuition has risen at twice the rate of healthcare costs and the public does not know why: true

- Learning outcomes and completion rates have gotten worse: true

- Grade inflation has devalued diplomas: true

- Students are not told that their degrees do not entitle them to a high-paying job: true

What nobody is told, for example, is that universities like the University of Chicago have reconstructed their approach to college football to make sure that it supports the academic mission. Or that a college education can be worth a lot to a student who studies at the right school and majors in the right subject. It doesn’t matter. Two million times, a story with elements of truth beat like a drum the message that higher education is not worthy of public support. What do we say?

Here is how I answered that question last year:

How do American universities respond? Meekly. As reported in the Chronicle of Higher Education, university leadership has been slow to recognize the direction and force of prevailing winds. A common mistake in business and politics is to focus on the feel-good stuff that is ultimately valueless, and universities are making the same mistake. The Chronicle reports that former MIT vice president John Curry told a gathering of heads of public universities to stop clinging to “worn out myths about campus strengths.” Curry told the group, “We like our stories more than the truth.” That leaves a vacuum for others to tell their versions of the truth. It was devastating to Goldwater and it will be devastating to higher education.

Facing the truth is an important part of focusing on the value of a university education, and Gerard Adams–the force behind “College Conspiracy”–knows that. He is the sympathetic interviewer. He is also president of the National Inflation Association (NIA), which produces not only “College Conspiracy” but other doomsday videos predicting hyper-inflationary consequences of monetary policy, healthcare reform, and food prices. What NIA is really all about is promoted prominently on their website:

Our goal is to help as many Americans as possible become aware of the disaster we are rapidly approaching. In our opinion, the wealth of most Americans could get wiped out during the next decade, but it will be an opportunity for a small percentage of Americans to become wealthy by investing into companies that historically have prospered in an inflationary environment, such as Gold and Silver miners and Agriculture producers.

NIA is a fringe group,and their activities are under scrutiny. But two millions viewers is a lot of viewers. Add to Gerard Adams conservative economists like Richard Vedder, who says through his organization Center for College Affordability and Productivity (CACP):

The pell-mell investment in sheepskins is beginning to look an awful lot like something our economy has seen in real estate: a debt-fueled asset bubble. It might end just as badly.

CACP has a message that is capable of reaching mainstream Americans. On the September 16, 2011 edition of the NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams, Richard Vedder’s voice was the one that reached 7 million viewers. He said college was “less good” as an investment. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg said, “College kids can’t find jobs and that could lead to riots in the streets.” And then there was an anonymous student who said to all of Brian Williams’ 7 million viewers: “College is a scam.”

Add the NIA audience to the NBC audience and you get roughly 10 million viewers. “Picking Daisies” was watched by an audience of 50 million. The Republican response was to complain about the fairness of the ads, but a week after the ad aired, a Harris poll found that half of all Americans believed that Barry Goldwater would involve the US in a nuclear war. What will be the response of higher education to “College Conspiracy”?

Others will define you if you don’t define yourself.

#change11